Before the onset of the pandemic, millions of people across the country lived in households without consistent access to adequate food. In fact, the United States Department of Agriculture estimates that 37.2 million people, including 11.5 million children, in the United States lived in food-insecure households in 2018. Although the prevalence of food insecurity in the United States had declined to levels not seen since before the Great Recession, COVID-19 will likely reverse these gains in food security.

To develop effective strategies to reach people at risk of hunger today, and in the future, it is important to understand what hunger looked like prior to the pandemic. Below is an overview of the state of local food insecurity before the onset COVID-19 along with projections of local food insecurity rates in 2020 due to the coronavirus crisis.

The State of Local Food Insecurity Before COVID-19

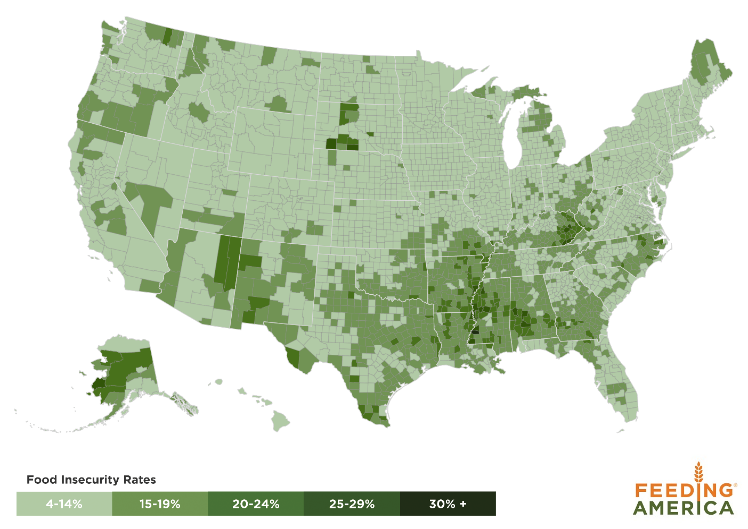

For the tenth consecutive year, Feeding America released the annual Map the Meal Gap study to improve our understanding of how food insecurity and food costs vary at the local level. The study uses publicly available state and local data from the U.S. Census Bureau and Bureau of Labor Statistics on socioeconomic and demographic factors that research has shown to either directly or indirectly contribute to food insecurity.

For the tenth consecutive year, Feeding America released the annual Map the Meal Gap study to improve our understanding of how food insecurity and food costs vary at the local level. The study uses publicly available state and local data from the U.S. Census Bureau and Bureau of Labor Statistics on socioeconomic and demographic factors that research has shown to either directly or indirectly contribute to food insecurity.

Prior to COVID-19, all 3,142 counties and county equivalents and 436 congressional districts in all 50 states were home to people who struggled with hunger. The percentage of the population estimated to be food insecure in 2018 ranged from a low of 3.6 percent in Burke County, North Dakota up to 30.4 percent in Jefferson County, Mississippi.

Counties with the highest rates of food insecurity (top 10 percent) tend to be disproportionately rural and located in the South. This is largely due to persistently high rates of unemployment and poverty. Socioeconomic disparities exist in other parts of the country as well, but have a disproportionate impact on people of color, especially African Americans. As a result, food insecurity sheds light on systemic barriers caused by structural and institutional racism and discrimination.

Projecting Local Food Insecurity in 2020 Due to COVID-19

Using the model developed for Map the Meal Gap, Feeding America has projected how food insecurity may increase in 2020 because of the economic impacts of COVID-19. We currently estimate that an additional 17.1 million people could be food insecure in 2020 as a result of this crisis – totaling 54.3 million people, or one in every six people. We also estimate that the number of children at risk of hunger could rise by 6.8 million to a total of 18 million, or one in every four children, by the end of 2020.

Locally, we estimate that food insecurity will increase in every county, congressional district, and state because of COVID-19. States with the highest projected food insecurity rates in 2020 are largely consistent with rankings based on 2018 rates. The one exception is Nevada, which moves from 20th to 8th highest due to the state having the largest projected increase in unemployment because of the pandemic. Nevada also ranks among the states with the largest projected increase in child food insecurity, jumping from 9th to 3rd. The other state with a notably higher projected rate of child food insecurity in 2020 relative to 2018 is Hawaii, jumping from 19th to 10th highest.

Program and Policy Implications

Federal nutrition programs, such as SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), continue to serve as the first line of defense against hunger in this period of increased need. However, not everyone who is food insecure qualifies for these programs or receives adequate benefits. This reality underscores the importance of both supporting charitable programs that help to fill the gap for millions of individuals and families and protecting and strengthening existing federal food assistance programs.

There are three concrete steps that the Congress and the administration can take to further invest in our federal nutrition programs to help households keep food on the table during and after the pandemic and resulting economic downturn:

- Boost the maximum SNAP benefit by at least 15 percent;

- Increase the minimum SNAP benefit from $16 to $30; and

- Suspend all SNAP rules that would eliminate or cut SNAP benefits for people facing hunger

The Feeding America network of food banks is working tirelessly to help feed every person without enough to eat. But we can’t do it alone. It will take all of us – from the charitable sector to our government – working together to ensure no one goes hungry in this unprecedented crisis.